You are highly regarded for your research in business, economics, and financial history. Looking back, how did you come to be interested in these subjects?

I went to college in 1968 with the idea of becoming a mathematician. At the time, the country was in the midst of the Vietnam War. Math began to seem to me a little removed from world affairs. I wanted to study something more connected to the world. I eventually settled on history as my undergraduate major.

When I attended graduate school, we were in the era of the birth of cliometrics, or the “new economic history.” This more quantitative approach to economic history was perfect for my interests.

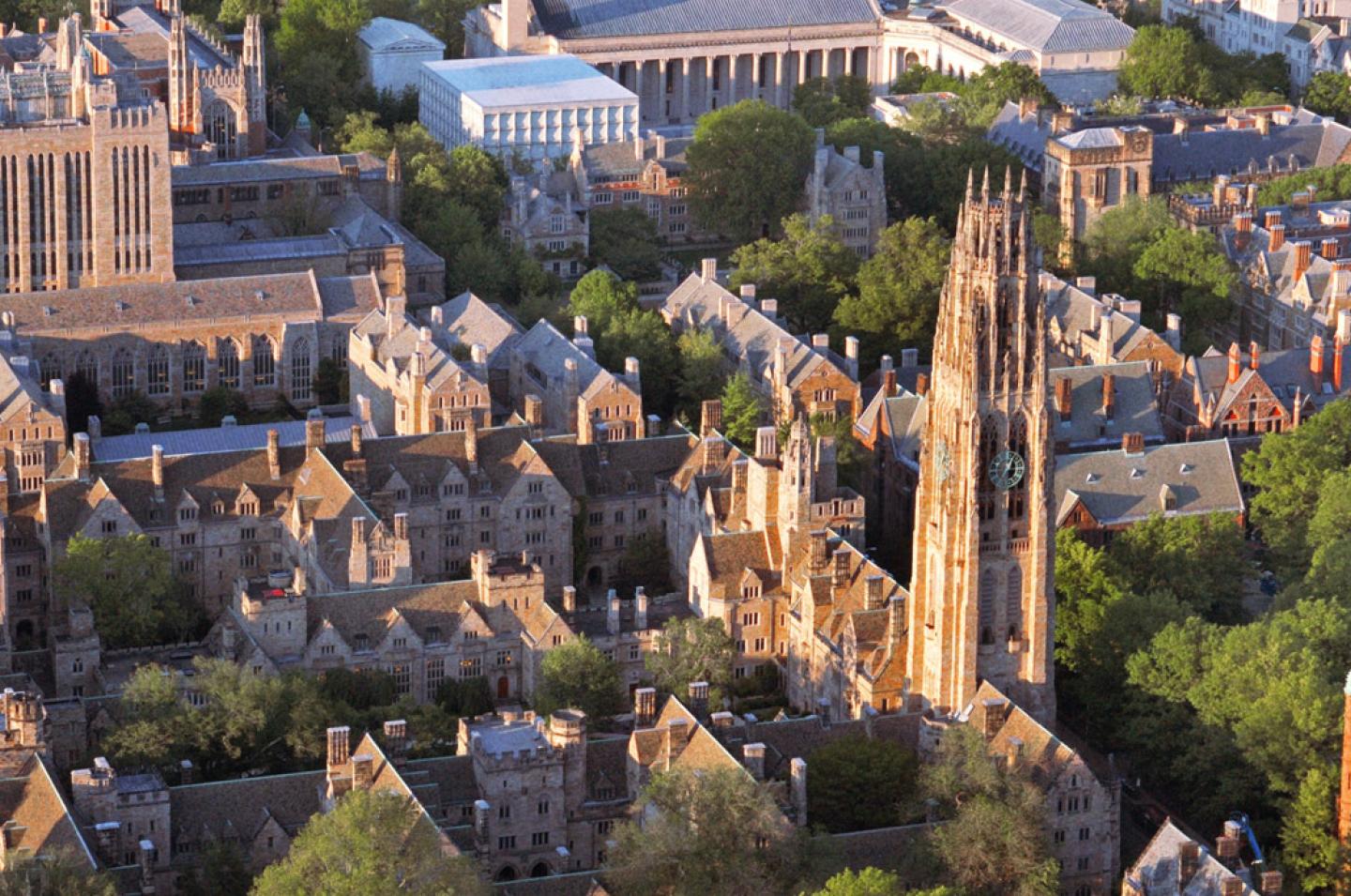

My PhD is in history, and my first job at Brown University was in history, yet I’ve always had very close intellectual contact with people in various economics departments around the country. Still, I was quite surprised when UCLA recruited me for their economics department. I said to myself, “Wait a minute. They’re going to wake up and wonder why they’re hiring someone with a PhD in history.” But it worked out. In 2010, Yale recruited me for economics with a joint appointment in history.

I think it’s tremendously broadening to have a foot in different disciplines. My whole career has prepared me for interacting with people who do very different kinds of things. I love it.

What are you working on now?

I’m very excited about a long-term project I’ve been working on with John Wallis, an economist at the University of Maryland. Our goal is to shift the grand narrative of US history away from the national government and the founding era to the states and the mid-nineteenth century.

One of the most important institutional innovations that shaped the American economy and politics was a set of constitutional reforms at the state level mandating that laws be general and apply uniformly throughout a given state. Before these reforms, eighty to ninety percent of laws enacted by legislatures were private laws benefitting specific individuals or groups, which greatly enabled political machines. As the provisions for general laws spread in the nineteenth century, they transformed the way government and the economy operated and interacted, giving rise to a more dynamic form of capitalism and economic regulation. The state that pioneered these changes was Indiana, believe it or not.

An extension of our project is trying to understand how general laws emerged in Britain, France, and then a little later in other European countries. The processes differed in each of these places, but the beginning and ending points were similar, and that is what mattered for how democracy functions.

You retired from Yale this past summer. What do you hope students will remember from your classes?

When I teach, there are two lessons I consider critical. The first is to think hard about quantification. For example, someone may cite a figure with a large number, and you immediately think, “Wow, that must be absolutely horrible, or absolutely incredible.” But numbers only have meaning relative to other numbers. You can’t tell if something's large or important until you have a standard of comparison. When you rigorously compare numbers, you begin to see that different standards of comparison change your interpretation. You must ask yourself: Is this number large relative to the economy? To a person’s income? It’s important to have several standards of comparison so you can think about what the numbers mean to people on the ground.

I also emphasize that you can’t only look for evidence that supports your argument. Whenever you’re making an argument, you need to keep a little devil on your shoulder who asks, “How would you know if you're wrong? How would you know if you're right?” And then you must consider if there is evidence for the argument that would prove you wrong.

Do you have favorite memories of working with students?

I’ve hired several students as research assistants over the years. Most of those relationships have been fantastic. One student asked to work with me while he was still in high school. I don’t usually hire high school students, but something about him convinced me. He ended up going on to enroll at Yale College and worked for me for his four years here. He graduated this spring, and although I’m retiring, I'll stay in touch with him, as I do with many of my former students.

What has surprised you most in your academic career?

That I can get paid for doing something so wonderful. Research is what I love doing, and teaching is amazing. It’s incredible to me that I get support for doing things that are this stimulating and fun.