Where do your interests in French and English literature and music come from?

I am British-Swiss and was brought up in a family with professional musicians. The connection between English, French, and music has been a part of my life since I can remember. Because my family traveled a great deal when I was a child, my language background also includes German, Urdu, Tamil, and Marathi—a whole mix of Western and non-Western languages. As soon as you start talking about what languages people use, you touch on the heart of their sense of identity—social, political, or aspirational—and their relationship to the world. There’s nothing superficial about asking people about that relationship because it is often a very complex one.

Why did you choose to focus on literature and music from the medieval era?

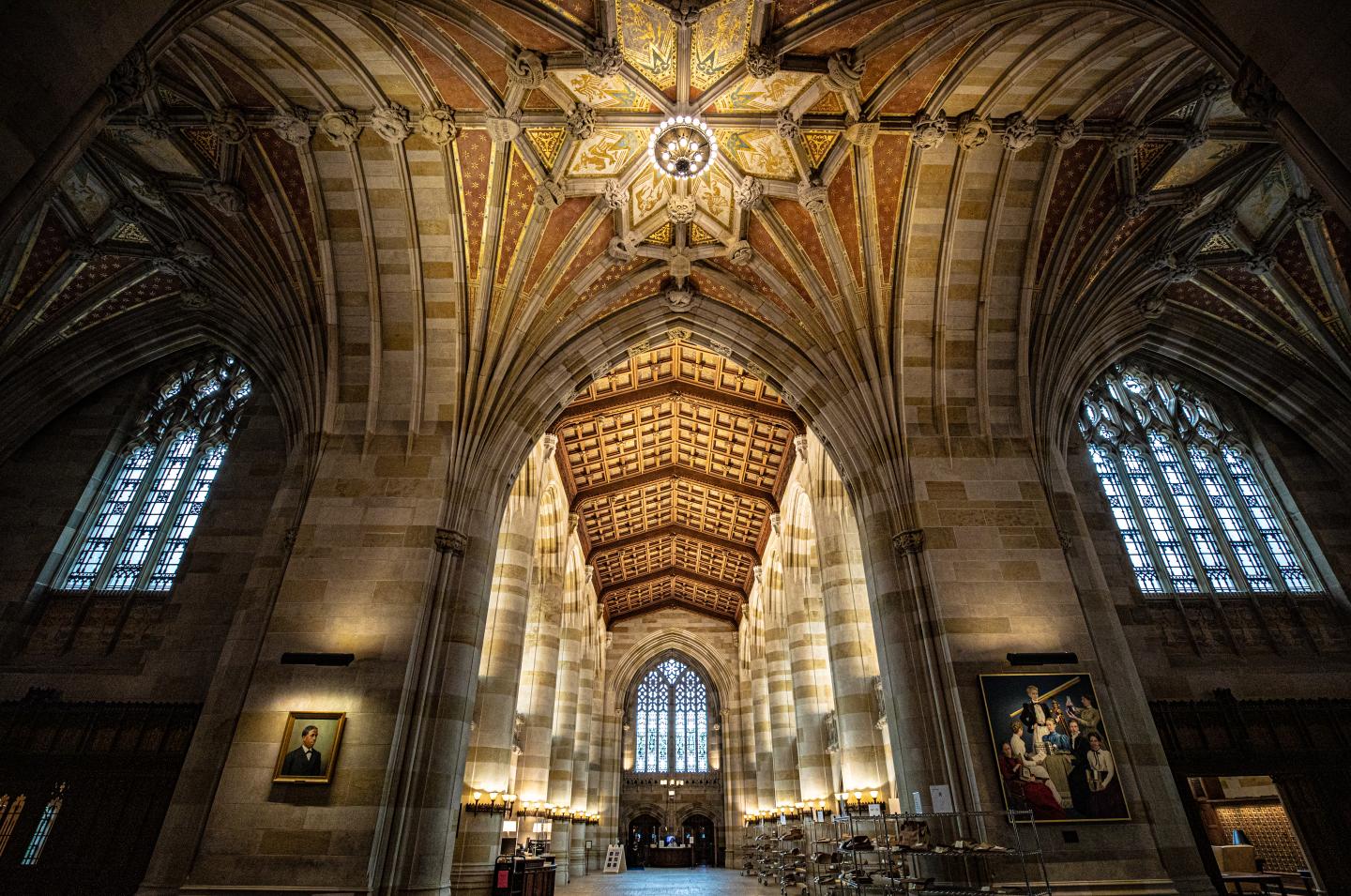

In Britain, and Europe more generally, you can walk into a six-hundred- or eight-hundred-year-old building or church. You can open a book just as old. You can see artworks from the same period. These things are not only in museums; they’re part of everyday life. I’ve always been fascinated by the intellectual and emotional issue of how we relate to objects from the past and how we articulate that experience. When it comes to music, however, we can’t access anything to do with how music sounded before the age of recording. There’s the historical puzzle in a nutshell. Our way of accessing medieval music is entirely in the present, through performance and interpretation. It’s critically important to me that, as a scholar, I do not retreat into the past but rather engage with it now.

What insights do you hope students gain from your classes?

I’ve found in my teaching there is a real hunger among my students to redefine how we interpret nearly everything: issues of race, gender, class, social positions, status, economy, and so on. Turning to the medieval past takes us out of contemporary preoccupations—which then opens those preoccupations to proper examination.

Medieval literature is certainly not considered “canonical” by current students. When they first see a medieval text, their reaction is often, “What is this?” It’s a shock for them when they can’t read it straight away, even though it’s written in English. They must look at the language and re-learn how to engage with something they expected to be familiar. That exercise is a central key to thinking about so many contemporary problems and a pedagogic goal that has become more and more important to me.

Do you have favorite memories from your time at Yale thus far?

One of my favorite anecdotes is from my very first term, when I was teaching a class called Major English Poets. (We've since rebranded and reconceived the course.) One of the students offered to present on John Donne, whom I’d describe as a very forceful poet of enormous personality. This student, who was a biochemistry major taking my class to fulfill a requirement, asked me, “Do you mind if I do my presentation through graphs?” She then made a brilliant presentation using two graphs on the blackboard, which completely transformed my understanding of the poem. The graphs were particularly apt because there was no massive distinction between sciences and humanities in Donne’s period. Donne himself was fascinated by issues of perspective science. The poem we were studying was about compasses and measuring the distance between worlds. This student was interpreting those ideas in a way I hadn’t expected. We all benefited from her presentation.

Another surprise to the story: the same student wrote to me about five years later to say she was applying to pursue an MPhil in Victorian poetry and Chaucer at Oxford. I saw her there this past year, and she’s now completed her PhD. For me, that made for a very special trajectory.

What projects are you working on now?

My new edition of the Norton Anthology of Medieval English Lyrics is nearly done. This project, an update of the original 1974 anthology, represents ten years of labor. I’ve gone back to the manuscripts themselves and re-thought the framing and approach of the anthology in profound ways. One key selling point for my edition is that it presents a broader sense of English—as well as Welsh, Cornish, Scottish and Irish—within the multilingual culture of Britain in the twelfth through fifteenth centuries, when French and Latin were the primary languages in literature and in terms of social status. The anthology will also probe the question of what “lyric” is, and it will take account of surviving music. As readers page through the volume, they will encounter texts that challenge conventional delineations of the category: curses, religious pieces, magic, prayers, language puzzles and much else. The anthology has been a lot of work, but it’s been a tremendously valuable experience.

I am also working on a short book on medieval song for the Cambridge Elements series and a more ambitious multimedia project geared for a larger audience. This one will track lines of song more broadly, examining links with non-Western and Western materials from throughout the Middle Ages. My hope is the project demonstrates to readers my fascination with medieval song in an accessible and comprehensive manner.

What does it mean to you to hold the Marie Borroff professorship?

I was incredibly moved to be named to the Marie Borroff chair. She was still alive when I arrived at Yale and attended one of my lectures in her wheelchair. The more I’ve learned about her—that she was a musician, a poet, a translator, and a pioneering scholar—the greater the honor of holding this chair. There’s an extraordinary photograph of Marie from 1967 in which she is surrounded by the other English department faculty, all men. To me, it’s an iconic and inspiring picture of independence, originality, determination, and intellectual brilliance. I should also note that my now-retired colleague, Roberta Frank, whom I could not admire more, held this chair previously. To hold a chair that has been shaped by the achievements of these two women is a tremendous gift.